Difference between revisions of "Ubiquitous Computing"

Caseorganic (Talk | contribs) |

Caseorganic (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

Technosocial devices compress the space and time needed to connect to information sources. Wireless, Internet-enabled devices allow ubiquitous connectivity to a omnipresent net of data, from which we can call up any piece of data we desire. No longer do we need to seek out the nearest phone booth or wait for a specific feature to play in a movie theatre – we can use mobile devices to play a clip, or use communication features to connect anywhere, at any time, in a variety of ways (both textual and auditory). Our ears can reach to the next neighborhood or Japan at the mere touch of a button. | Technosocial devices compress the space and time needed to connect to information sources. Wireless, Internet-enabled devices allow ubiquitous connectivity to a omnipresent net of data, from which we can call up any piece of data we desire. No longer do we need to seek out the nearest phone booth or wait for a specific feature to play in a movie theatre – we can use mobile devices to play a clip, or use communication features to connect anywhere, at any time, in a variety of ways (both textual and auditory). Our ears can reach to the next neighborhood or Japan at the mere touch of a button. | ||

| − | |||

Information has become an extension of our brains into this connected, dynamic 4th dimensional field that we can only see when we ask for a part of it. The entirety of it cannot be felt or accessed at one time, and our interfaces are still limited in the fact that we can only access this data via flat, two-dimensional screens. “I have become a roaming subscription number. As my feet slide upon thousand-year old stone, I am at once travelling through networks and central servers back in Australia, my details handed on via invisible network handshakes across the globe, my trajectory recorded. I am not lost, I am identifiable; I am a string of information events".{{citation needed}}<ref>Infomobility and Technics</ref> | Information has become an extension of our brains into this connected, dynamic 4th dimensional field that we can only see when we ask for a part of it. The entirety of it cannot be felt or accessed at one time, and our interfaces are still limited in the fact that we can only access this data via flat, two-dimensional screens. “I have become a roaming subscription number. As my feet slide upon thousand-year old stone, I am at once travelling through networks and central servers back in Australia, my details handed on via invisible network handshakes across the globe, my trajectory recorded. I am not lost, I am identifiable; I am a string of information events".{{citation needed}}<ref>Infomobility and Technics</ref> | ||

Revision as of 03:25, 31 July 2011

Definition

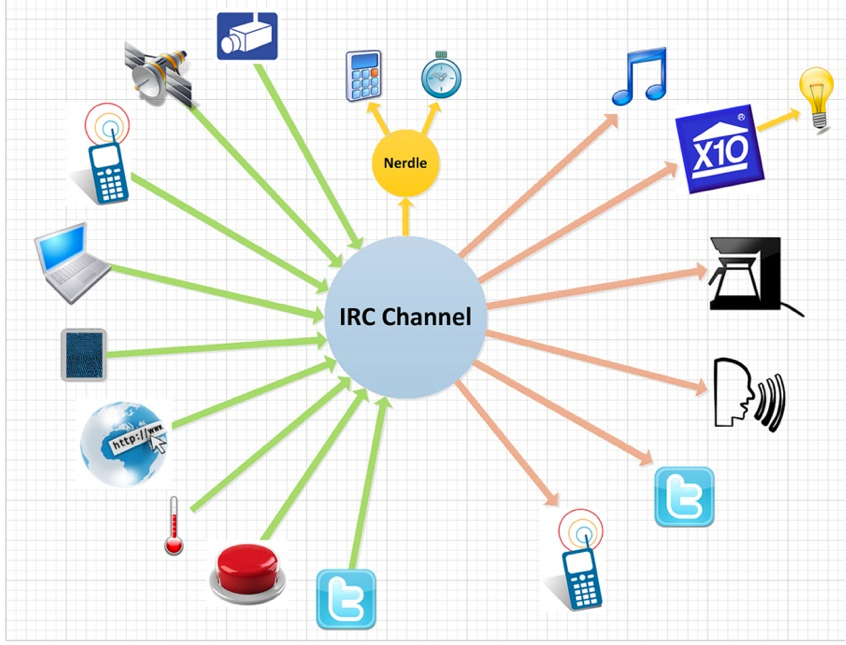

Ubiquitous computing is a term used to describe the growing ability for devices and objects to be able to communicate with each other over protocols embedded in everyday objects.

In the 1980’s, researchers at Xerox Parc talked about “the inevitable withdrawal of the computer from the desktop and into a host of old and new devices, including coffeepots, watches, microwave ovens, and copying machines. These researchers saw the computer as growing in power while withdrawing as a presence”.[1]

Ubiquitous technologies compress the space and time needed to connect to information sources. Wireless, Internet-enabled devices allow ubiquitous connectivity to an omnipresent net of data, from which we can call up any piece of data we desire. This system is both decentralized and centralized, in that we can get data from the centralized location of our handheld device, but we ourselves are decentralized in relation to the actual location of the data. This leads us to a unique moment in human history – that many of us now have the ability to be omniscient and omnipresent at the touch of a button. The omnipresent information net can snap data to us from almost anywhere.

Functionality has also become centralized. Pieces of analog technology that use to serve us in these ways have suddenly merged into one liquid device. Portable electronic dictionaries and translators are now available as software on one device instead of multiple devices. It is the equivalent of the door-to-door Encyclopedia salesman being taken out of a job by the CD-Rom, and later, Google and Wikipedia. Everything – all accessibility – is now available in one device – one place.

Technosocial devices compress the space and time needed to connect to information sources. Wireless, Internet-enabled devices allow ubiquitous connectivity to a omnipresent net of data, from which we can call up any piece of data we desire. No longer do we need to seek out the nearest phone booth or wait for a specific feature to play in a movie theatre – we can use mobile devices to play a clip, or use communication features to connect anywhere, at any time, in a variety of ways (both textual and auditory). Our ears can reach to the next neighborhood or Japan at the mere touch of a button.

Information has become an extension of our brains into this connected, dynamic 4th dimensional field that we can only see when we ask for a part of it. The entirety of it cannot be felt or accessed at one time, and our interfaces are still limited in the fact that we can only access this data via flat, two-dimensional screens. “I have become a roaming subscription number. As my feet slide upon thousand-year old stone, I am at once travelling through networks and central servers back in Australia, my details handed on via invisible network handshakes across the globe, my trajectory recorded. I am not lost, I am identifiable; I am a string of information events".[2][citation needed][3]